What do you hear in the snow, Signore Abbado?

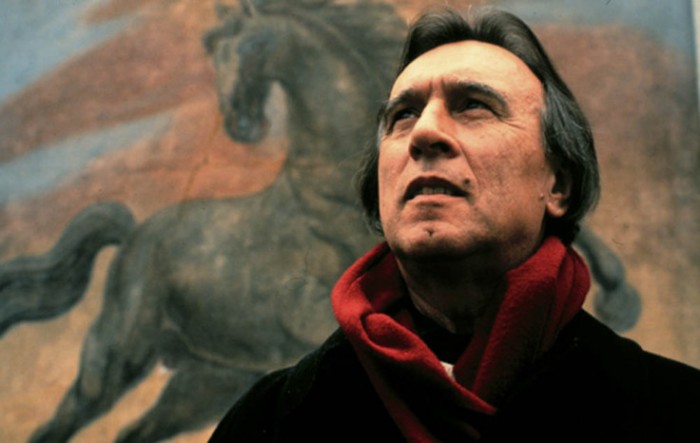

We talk to the conductor Claudio Abbado in his hotel suite in Berlin. In front of us are scores and musical manuscripts. Abbado radiates great calm and an exceedingly kind, gentle charm. He talks with a melodious, very quiet voice.

What are these manuscripts lying in front of you and which you are studying?

They are notes by Alban Berg concerning his Lulu-Suite which I have received recently. There are entries in the score which are very interesting.

You have conducted this score so often since 1964. Do these notes change anything in your interpretation?

Yes, of course! You keep on finding something new. Look at this wind passage for example: “leierkastenmäßig” (like a hurdy-gurdy) is written there. This indicates to me that this theme must be played in a “Viennese” way.

You study scores very thoroughly

Yes, much can be learnt in this way. Often too through the corrections that the composers have inserted themselves. Mahler infers half of his life in his scores, his jealousy, his great love. That is very informative. Poor Mahler suffered so much. His wife Alma was not exactly easy…

Lately her compositions have been discovered and it has been claimed that she was suppressed by Gustav Mahler

What do you think of Alma Mahler’s compositions?

They are not really significant

Exactly. In Edinburgh I once instigated a Mahler-Festival in which compositions of Alma were also played. I realized at the time that she was a good student –but not more. However she really thought she was the greatest. That was due more to her character than to her talent.

Has the Mahler year brought you any more insights?

Yes, but just as every other year does. Anniversaries are only an occasion.

Mahler’s music has always sparked off discussions whether it is “absolute” music or “programme music”. Do you see any sense in this differentiation?

In my opinion everybody can decide for himself. For me it is simply wonderful, great music which I love. I need no label for that.

And what about Mahler’s programmatic entries? Do you make any use of them?

These do give you new ideas. But that is exactly the lovely thing about great composers: that you forever find new aspects in their works. Great music is inexhaustible. In music, like in life, there are no limits. That is why I always try to restudy a score as if it were for the first time. Anything else would be too easy – and too boring.

How does a great conductor avoid routine?

Firstly: you just must avoid it. And secondly: the term “great conductor” means nothing to me. It is the composer who is great. We are only the servants of the music and have the obligation to understand as much as possible.

You were friends with some important composers and worked closely with them. I am thinking here of Luigi Nono.

The cooperation with Luigi Nono was enormously important and instructive for me, also because we did many premières together. That gave me insight into how a composer thinks, what his thoughts about a composition are. And as a result I started thinking about the ideas of composers of more ancient works which I conduct too. Over and above that it is interesting to investigate what the conductors belonging to a composer’s inner circle of friends have to say. For example, the experience of Bruno Walter is of greatest value. Walter, who since 1894 was Mahler’s assistant in Hamburg, who followed him 1901 as conductor to Vienna and who conducted the first performances of “Das Lied von der Erde” and the 9th Symphony, wrote much about Mahler. Or think about Arnold Schönberg’s text concerning the Viennese school and also Mahler. Nuria Nono-Schönberg continuously makes discoveries in her inheritance. It is very instructive to read that Mahler thought it would take half a century to understand his 6th symphony. Indeed you really need much time to penetrate into the secrets of such a score. Or think of the leap Schönberg made between Pelléas et Mélisande or the Gurrelieder and his last works. That is really tremendous. In his early works Schönberg already uses twelve tones – as did others before him – but he only developed the structure and the method of twelve-tone music much later.

They only serve there as basic material, not as a principle of form.

Once you have seen that you can discover these principles in all ancient music: in Bach of course, but also in Gesualdo. Gesualdo was the most modern of all. Look at the way he treats the rules of the use of dissonances. That is bold! Bach was completely thrilled. It would be highly interesting, by the way, to find out how they communicated. As far as I know Bach was never in Venosa or indeed in Basilicata. Have you ever been to Basilicata?

No, never

You must go there! I was there for the first time only fifteen years ago. But that was like a new world for me. Nobody ever talks about this region of Southern Italy, but it is very interesting. There was a big Greek influence there, later of course a Roman one too. Real architectural riches can be found there, marvellous amphitheatres for example.

In the finals of the German Conductor Prize I noticed once again how many different things must be taken into consideration whilst conducting: knowledge of the score, the beat, gestural and mimic communication. How does one learn all that?

The wish to make a career is surely the wrong precondition. The most important is a deep love of music. Karajan, who was like a father to me, gave me much good advice. He heard me with the former Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin and invited me to Salzburg. There I conducted, on my request, Mahler’s 2nd Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic. That is how it all began. Karajan always advised me not to do too much and to conduct only if I was completely sure of myself. He warned me against a mistake he had once made himself as a young man: to stand on the rostrum with an insecure feeling.

Unluckily there are many examples of young artists who cannot resist the temptation of a quick career

Yes indeed, one has to be very wary of the strategy of the record companies. When Deutsche Grammophon suggested a cycle of all the Mahler symphonies to me I accepted only on the condition that I was allowed to take my time. Meanwhile I have recorded them all three times.

Do you sometimes listen to your old recordings?

Yes. Sometimes it is not too bad, sometimes it is dreadful.

Your understanding of Mahler then has changed?

Of course. I penetrated deeper and deeper.

Are you interested in any contemporary composers?

I worked with Nono, Boulez, Berio and Stockhausen when I founded the festival “Wien Modern”. Then there was the young composer Wolfgang Rihm with whom I like to work. He is such an intelligent composer and cultured man. With Henze I did a few things too.

What do you do when you do not work?

I go into the mountains, to the Engadin in Switzerland. There is a lovely valley there, the Fextal, where for the past hundred years nothing has been allowed to change. There is no traffic, you have to reach it by barouche or on foot. Every summer I go on long walks there which are ideal for studying.

How do you study during a walk? You must have the music in your head?

Yes, I let the score pass through my head and repeat everything inwardly. This countryside is so marvellously quiet. Even in summer there is snow there. And I love the sound of snow.

The noise it makes when one treads on it?

No, you can hear it even if you are only standing on a balcony.

You can hear snow?

Of course it is only a minimal, not even a real noise: a breath, a trifle of a sound. You have the same thing in music: if in the score there is a pianissimo marked that ends in nothing. Up there you can feel this “nothing”. With an orchestra it is very difficult to achieve it. The Berlin Philharmonic manage it sometimes.

Is it indiscreet to ask you about your present state of health? You definitely look very well.

I am very much better. Of course I need a lot of discipline, in particular concerning meals. But also in my work. I do not give so many concerts any more: Berlin, Lucerne, Orchestra Mozart – that is about all. And with them I make my recordings.

But now you also want to introduce the Venezuelan training programme “El Sistema” in Italy

In some places it is thriving already, for example in Bolzano where there are three thousand applicants. We have something resembling a network in various Italian towns. In Milan it is very well organized by Maria Maino, in Fiesole by the pianist Andrea Lucchesini. In Naples it is still difficult at the moment, I will have to go there myself next year.

A quite different question: does such an experienced conductor like you still suffer from stage fright?

Of course, always. But from the start, already during my years at La Scala, my maxim was always to concentrate on my work, i.e. to support the soloist and the singers on stage or the composer whose work I was performing. Because the pressure on them is far greater than on the conductor. It helps to divert the attention from your own situation.

Do you feel your talent as a duty, an obligation to pass on your understanding of music?

Yes, I have always done that. That is, for example, why I so admire José Antonio Abreu who invented the “El Sistema” programme. What he got off the ground in Venezuela: he put 400 00 young musicians on the path to music. And he is increasingly expanding his activities: to Brazil, Mexico – one of these days the whole of South America will be full of music thanks to his commitment.

Julia Spinola

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 9.7.2011